|

|

|

Hilary said, “Bart is making a maquette for Wild Imaginings.”

“We have to have one,” said Loie. And that was the start of that.

Bart had sketched the concept for the full sized for Loie’s boss Darrell Batson, director of the Frederick County Public Libraries, back in 200?. Darrell was hoping to add a sculpture to the entrance of the main library during its marathon renovation. Unfortunately the Friends of the library thought the offered price was too high. Bart later revived the wonderful concept, sold several and now was creating a maquette for those of his collectors for whom the full sized would be a bit too ambitious.

“I’m going to keep it in my office,” said Loie. “We’re finally going to have a Wild Imaginings at the library.”

“I wonder if we could see it cast?” I said.

“Sure,” said Hilary. “Well, I’ll see if we can find out. The foundry schedule is kind of changeable.” In the end it worked out that I had time off on the day of casting. Loie couldn’t go. So I took her camera down to New Arts Foundry on a blisteringly hot Baltimore summer day.

|

|

Bart Walter's new Wild Imaginings Maquette. Bart Walter's new Wild Imaginings Maquette.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tucked away on a dead end street in a classic working neighborhood, at 3:30 in the afternoon the foundry’s cinder block building was baking inside and out. Inside, the baking was literal: a four foot wide squat cylinder was spewing flame out its top. Nearby, a big metal box was held up on the forks of a towmotor lift while a blue hot flame seared the bottom of the box. It was hot. But it was going to get hotter.

I had wandered in an open door directly into what turned out to be the casting room. It took a minute for the foundry’s director to wander through a pair of big swinging wooden doors. I introduced myself and it seemed I was expected. Hilary had done well on that score. It took a minute to convince Gary that I wanted to see everything, get a grand tour. He graciously led me back into a thankfully airconditioned part of the foundry and walked me past all the stages of the casting process. I took some pictures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“But you can’t photograph the whole thing,” I was warned. “We don’t have the rights to the whole thing.” I cheated a bit in the finishing room, where a set of Bart’s was nearing completion. Having been the graphic designer and webmaster for Bart for years, I didn’t think he’d mind my adding a few more candids of his work to the hundreds of images already on my computer.

And now I have to make a confession. In spite of Gary’s kind and patient efforts at explaining, my recollection of the details of the casting process are hazy. The many steps of reproducing an artist’s original in first, I think, a rubber coating, then surrounding that somehow with plaster, then using the rubber to create a wax model; the cutting of the original into parts, putting the wax reproduction back together into a whole; cutting that up again…it was too much too quickly.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

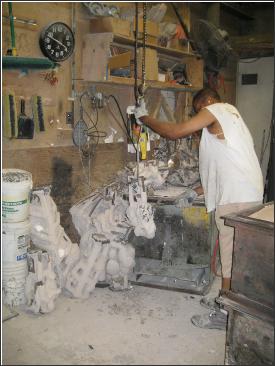

Along about the time we hit the slurry room, I kind of started to piece it together. Somehow, through all these processes, a perfectly faithful wax reproduction had been made of Bart’s original clay model. And I mean perfect. Fingerprints had been preserved. Except that the wax was in pieces. Wild Imagings Maquette was requiring three.

The wax pieces each had a metal trumpet with tube arms attached to them. This whole weird assembly was now going to be coated in ceramic slurry, in a machine that somehow spit the glop all over the assembly. I caught on to the fact that the molten bronze was going to be poured into the trumpet, gurgle through the arms and into the ceramic surrounding the wax piece.

“Oh,” I said, “The lost…”

“Lost wax process," said Gary. Yes. Except the wax gets lost when we bake the mold.” My puzzlement must have been obvious.

“Out here.” And we walked through a door back into the big hot casting room. Full circle.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

“Up in here. The molds are baking, and the wax is burning out. We've got more than one mold per piece. We put them together, so the sculpture can be hollow. Less metal.”

I was being shown the big metal box on the forklift, with the flame under the box. Finally it all kind of came together. Although I was still hazy on the beginning steps, obviously the whole process was intended to get to this point: baked, hardened ceramic molds, capable of containing molten metal—and what other material besides ceramic could contain molten metal?—whose insides were an exact casting of Bart’s original clay.

It was a ballet, even an art form all its own. The precise interplay of all these materials, Bart’s malleable clay, the stretchy rubber, brittle plaster, soft wax, sludgy ceramic slurry baking hard, dense rough metal becoming molten was astounding. The precision being maintained through all these permutations of liquid and solid, the dismemberment and piecing together, and postive and negative reproductions flabbergasted me. Who had ever figured this all out?

"I guess people have been doing this a long time," was Gary's answer to my musing aloud.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

When I had returned home and called Hilary, madly enthusing over what I had seen, she said, “Bart says he feels like he’s directing a symphony when a piece is cast.” Not a bad metaphor, but it doesn’t capture the multitude of changes of states of materials, the back and forth of insides and outsides involved. Perhaps there isn’t any metaphor that captures the whole thing. Maybe it’s just something of its own.

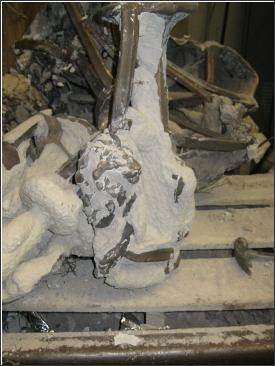

But at the foundry, the best was yet to come. In the casting room, a pile of castings was jumbled next to a metal table, and I was told a piece of a Wild Imaginings Maquette was in the heap.

“Which one,” I said. “Can I get a picture?” One of the foundry employees kindly used an electric winch to hoist out an unrecogniseable contraption of trumpet and tube arms and melon sized lump all covered with lumpy rough ceramic. He took up a hammer and started to beat on the ceramic! As bits and crumbs flew off, I saw dark metal emerge. He hoisted the casting onto the table, and said, “There’s the face.” Only a small amount of the ceramic had been chipped off. I was still looking at a lumpy assemblage. I had to peer. And then I saw it, the lion’s face, with ceramic still crusting the indentations, but our lion’s face none the less.

Or perhaps someone else’s lion. At first I wanted to think this was our lion, but then I was being advised to keep back behind a certain point during the casting. Which, in the wonderment of all the preparation for it, I had almost forgotten. No no. The lion on the table was someone elses’. I was here to see our lion cast in bronze.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

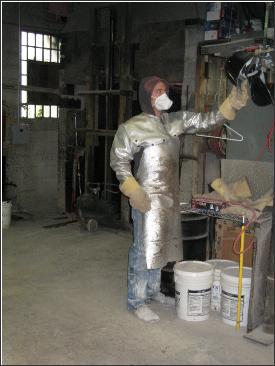

Now it got hot. The front door was closed. The big fan was shut down. The furnace I had noticed at first was cranked up, its fire now burning green. Foundry workers put on metalized aprons, face shields and huge leather gloves. The ceramic baking forklift was driven around; a six foot by four foot by four foot metal box was filled with sand. The workers took blazing hot ceramic molds out of the forklift box and began bedding them in the sand box. Some of the molds were piled up around the lip of the still blazing furnace. I guessed the molds were being sorted by size, the larger ones went right in the sand box and the smaller put between them, all with their trumpets pointing up.

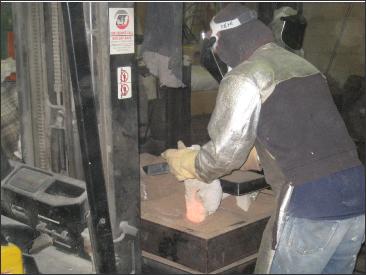

I was trying to make a little film recording when I realized Loie’s poor camera was hot. Not quite too hot to hold, but too hot for a camera to get. I popped behind the big swinging doors into the air conditioning for a few minutes, then back into the casting room just in time for the finale. Electric winches were pulling an urn—later I was told it’s the crucible—from the round furnace. A long-handled metal clamp was put around the crucible, and it was hoisted over to the sand box. Apparently the rig was balanced just so, because the workers in their metal aprons used a handle on one end of the clamp to tip the crucible over each trumpet in turn, jockeying the winch to position the crucible for each pour.

Brilliant fiery orange molten bronze streamed into the trumpets.

“Harder,” said one of the workers to the young fellow working the pouring handle. “Gotta go faster.” I thought he was referring to the speed of the metal filling the mold, not necessarily to the pace of the whole process. On the next, harder pour, bronze spilled over the trumpet into the sand.

“OK.”

About a dozen molds were filled, perhaps ten minutes passed. The heat coming from the crucible and molds was withering. And I was standing well back, as admonished. The workers must have been baked. I took pictures when I could, but kept the camera behind my back between shots.

Eventually the casting was over, the door opened and fan back on. The temperature began to return to just a normal Baltimore hazy, hot and humid. I thanked everyone for their time and patience with my questions. Cleaning up began. It was time to go home. Wondering all the way at the beauty of the molten casting, the precision and care, the mess and seeming confusion of castings all piled, slag heaps, heat, cool, a symphony, a ballet of art amongst the cinder blocks.

Wild imaginings, indeed.

|

|

|

|

|